Blue sky peeking out under rain clouds. Pacific Northwest perfection.

When I was an undergrad, I had this brilliant idea: The Lung Brush. This handy little device would remove the burden of moderation for party people everywhere. Chain smoke all night! Then simply brush away your hacking cough when you wake up the next day – whenever and wherever that may be – and you’re ready to paint the town red all over again!

After the last couple of weeks of wildfire smoke, I think this product would sell like hotcakes.

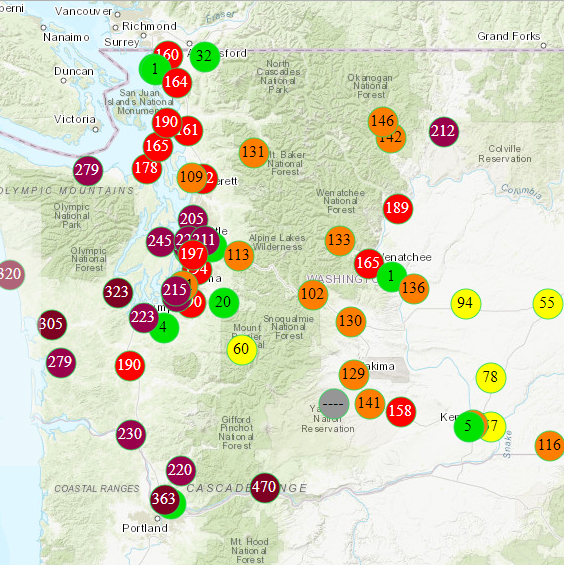

According to the Washington Smoke Blog, “…more Washington communities have been exposed to more hazardous levels of particulate pollution than we’ve ever seen since we began monitoring for PM2.5 (the most concerning type of particulate pollution found in wildfire smoke) back to the early 2000s.”

That’s a lot of potential Lung Brush customers.

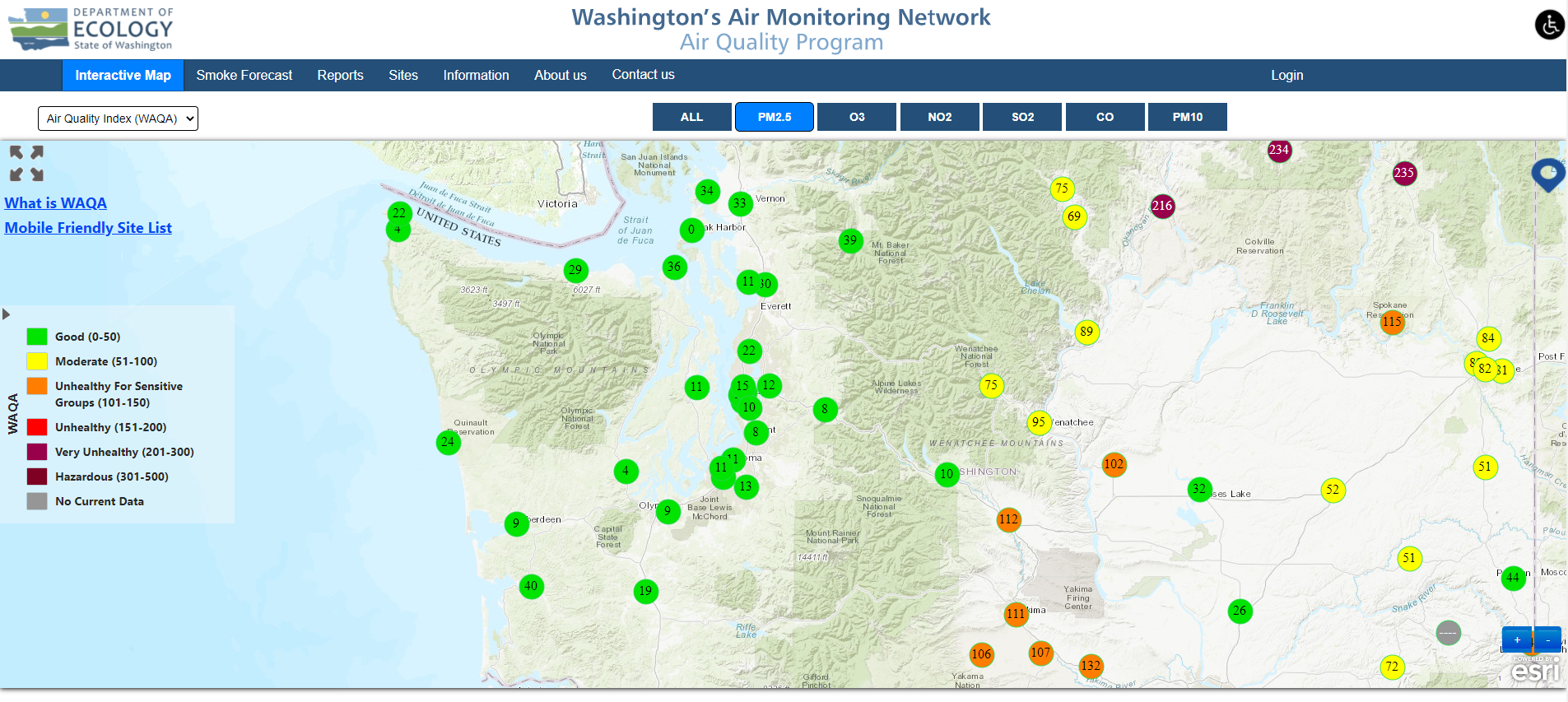

Waking up this morning to an air quality map showing Western Washington covered in green dots was cause to celebrate. But when we threw open the windows and doors, and I stepped outside in my jammies to take a deep breath, that partied-all-night feeling in my lungs got me thinking. Absent the Lung Brush, what should I do now that the smoke is gone, and what does that exposure mean to my health?

Hell yes! My Eastern Washington friends, I hope this trend continues and relief comes your way soon.

Let the outside in

You’ve been hearing the advice for two weeks: When it’s smoky outside, the best thing you can do is stay inside and keep the doors and windows closed. If you’re fortunate enough to have an air conditioning system, you’re supposed to set it to recirculate indoor air. Basically, keep the outside air out as much as possible.

But, unless your home is hermetically sealed, some smoke gets in. Plus, we do all kinds of things to dirty up our indoor air. Cooking produces smoke. Showering produces mold-promoting moisture. Don’t even get me started on woodstoves.

The point is that over the course of the last couple of weeks, the quality of our indoor air has hopefully been better than the outdoor air, but I’m willing to bet it was still pretty rotten for most of us. With all of Western Washington solidly in the green this morning, the air outside was certainly cleaner than the nasty air in my house.

Once the smoke is gone, the best way to clean the air is to open the windows and doors and let that outside air in.

I opened the windows around 7 a.m. and haven’t closed them since. It’s a little chilly, but I’ll put on a coat before I close the windows because I’m so relieved to get some fresh air in here.

If I have sparked a newfound interest in indoor air quality for you, I highly recommend the resources on the Northwest Clean Air Agency website, developed by Dave Blake over the course of his long and illustrious career. (He’s retired, but you can still benefit from his advice and dulcet tones in NWCAA’s impressive YouTube video library.)

The nitty gritty on ash and soot

When it comes to wildfire smoke, I tend to think about air quality. But what about surfaces? Did the smoke leave behind a layer of contamination I need to worry about?

A quick visual inspection tells me that the surfaces in my house are just as dirty as they were before the smoke. The dust on the base of my computer monitor is the same disgusting gray it was two weeks ago. The papers are still white. I don’t see cause for concern for anything except my poor housekeeping habits.

But, you might counter, didn’t you say in your last post that PM2.5 is microscopic – 1/3 the size of a human hair? I did indeed. And that microscopic particle size makes it light enough to float around in the air, get detected by air monitors and get inhaled deep in your lungs. If it’s heavy enough to fall on my desk and the carpet, I’m guessing it’s not PM2.5 and I don’t have to worry about breathing it in the same way I did when it was smoky. Dusting, vacuuming and sweeping throws a bunch of that stuff into the air, though, so when I do finally get around to cleaning, I’ll follow the guidance and use a damp towel or some kind of dusting spray in a can (which is probably worse for me to breathe than the dust itself), and vacuum with a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter. I’ll probably wear a mask because I have a wicked dust allergy. I figure any soot I breathe while cleaning isn’t any worse than the smoke itself.

But what about touching it? I did a little poking around online, and (not that this is any proof) nothing suggested indoor surface contamination should be a big concern here in Western Washington because we’re far away from the fires. If your home burned or was near a fire – especially a fire that burned buildings – then you have a different set of worries and different guidance to follow.

Information I’m seeing about gardens and veggies seems to fall along the same lines. If you’re far from the fires, you should be fine if you give the veggies a good rinse. If you’re close to the fires, especially where homes burned, then, again, you have more to worry about, including heavy metals deposited in the dirt.

But I’m no scientist, and I haven’t invested a ton of time trying to look up studies and do research. If I really wanted to do something about it, I’d probably swab the dusty base of my computer monitor and send a sample off to a lab for testing. This article in the November 2017 issue of the American Industrial Hygiene Association’s publication, “The Synergist,” talks about what one might test for.

But I figure if health officials aren’t posting alerts about what we can do to protect ourselves after the smoke rolls out, I can relax a little. I worry about a lot of things. Cleaning up after the smoke is gone isn’t one of those things.

The long-term effects

The residual effects of smoke on surfaces in my house is one thing. The residual effects of smoke in our bodies is something else entirely.

The whole reason air agencies monitor particulate in the air is because it’s bad for our health. I hear and read all the time that there is no such thing as a healthy amount of particulate. The U.S. EPA says short-term particulate exposure (a few days) can lead to serious health effects that include premature death. That’s pretty serious.

Why are they smiling??? I like the AQI chart in the background, though.

We just emerged from a solid two weeks of bad air. What does that mean for our health? Will my lungs recover? Did I just mess up my kid’s cardiovascular and respiratory systems for life by keeping her here during Smoke Storm 2020?

According to EPA, there isn’t a lot of information about what that exposure means long-term. A study of wildland firefighters suggests we can expect reduced lung function after several fire seasons – what EPA refers to as “cumulative short-term exposures.”

Then I ran across this story in Kaiser Health News yesterday about a study in Seeley Lake, Montana. Researchers set out to track the recovery of people who lived under a thick plume of wildfire smoke for seven weeks three years ago. But they aren’t seeing a recovery. Instead, researchers are tracking the decline in residents’ lung function.

In the story, Katheryn Houghton writes: “So far, researchers have found that people’s lung capacity declined in the first two years after the smoke cleared. Chris Migliaccio, an immunologist with the University of Montana and his team found the percentage of residents whose lung function sank below normal thresholds more than doubled in the first year after the fire and remained low after that.”

The researchers haven’t been able to go back to Seeley Lake this year because of COVID-19.

The story goes on to say that effects of wildfire smoke haven’t been explored much until recently, and that more research is needed to assess the health implications of repeated exposures.

With wildfire smoke turning into a regular summer occurrence here, I’m afraid there will be plenty of opportunities to conduct robust studies.

About that Lung Brush: Now how much would you pay?

Leave A Comment